Have you noticed the stairs to nowhere? Hiding in plain sight, in the center of the University of Houston campus, next to Philip G. Hoffman Hall, a concrete canopy protects the entrance to what looks like a Cold War bomb shelter. Now abandoned and gathering debris, this is a relic of the university’s soured love affair with underground buildings.

In the 1960s, the campus assumed a more suburban look; new buildings were widely-spaced, separated by expansive lawns and groves of trees. To preserve this park-like setting, university planners tried to hide new buildings beneath lawns or plazas. It was all very logical: A plot of land did double-duty, allowing the university to capture usable space for activities without losing precious open space outdoors.

During this period four buildings and parts of others were placed underground, but by 1980 this fad had run its course. What happened? Public tastes changed as Modern architecture, which brought us the underground buildings, lost favor to more traditional styles. More importantly, university planners recognized the dangers of flooding in low-lying Houston. Flooded streets have always been a nuisance, but flooding from Tropical Storm Allison in 2001 was unprecedented and caused millions of dollars in damage to campus buildings. Today the university does not put buildings underground, and new buildings do not have basements.

But in case you missed them, here are the present and former structures beneath our feet:

University Computing Center (early 1960s)

Buried a few yards north of the Ezekiel Cullen building is a facility that began life in the 1960s as the University Computing Center. When the university moved its mainframe computers to a new building on Elgin Street in 1976, this area became an office annex for E. Cullen. Allison filled it with water. Rather than repair the damage, the university locked the doors and abandoned it.

University Center Annex (1965)

In the mid-1960s the university spent a lot of money to dig a huge hole next to the University Center for an underground annex topped by a plaza. Fifty years later, as part of the UC renovations, the university spent a lot of money to fill in the hole and build the replacement structure on top of it. It has no basement level.

Architectural rendering of University Center with underground annex in foreground, mid 1960s. Photo courtesy of UH Buildings Collection, Digital Library.

Agnes Arnold Hall (1968)

From the south, Agnes Arnold Hall, a mid-rise tower, appears to rise from a large open courtyard located below street level. The building is reached by a bridge, which spans the courtyard below. In Allison the courtyard, a basement-level lecture hall, as well as elevators and escalators, were all flooded.

UH Law Center. Large plaza in background covers underground library. Central courtyards in classroom buildings on right also cover underground libraries. Photo courtesy UH Buildings Collection, Digital Library.

Law Center (1970)

The UH Law Center opened in the early 1970s with a group of two-story classroom buildings clustered around a large plaza. Beneath the plaza was the law library. Each of the classroom buildings had an atrium-courtyard; below it was a satellite library in the basement. In Allison the entire lower level flooded, causing catastrophic damage to the library collections.

University Center Satellite (1973)

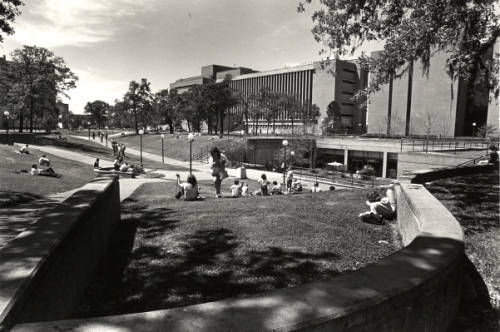

As the campus expanded to the northwest, university planners grouped the new science and fine arts buildings around a grassy quadrangle. Beneath this lawn was the new University Center Satellite, which provided dining and recreational facilities for students on this end of the campus. This building was inundated in Allison and remained closed for repairs for more than a year.

Hilton Hotel Parking Garage (early 1970s)

When the University Hilton and the adjoining School of Hotel and Restaurant Management were built in the 1970s, the complex included a parking garage. The garage is under the building, reached by a steep ramp from the street. Like all of the other underground structures, it flooded in Allison.

Students lounge outside UC Satellite, circa 1980. Sloped lawn directs water toward entrance. Photo courtesy UH Buildings Collection, Digital Library.

History is where you find it . . . often in bits and pieces . . . a puzzle to be assembled.

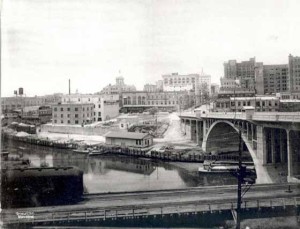

At the University of Houston Libraries, Special Collections we have one piece of the historical puzzle known as the Sunset Coffee Building. Only a few yards from Allen’s Landing, where the city was founded, this building has been a fixture downtown since 1910. A century ago its waterfront location permitted access to boats and barges headed to Galveston Bay and beyond. It had many uses over the years until it was abandoned and left to decay. In 2013 Houston First Corporation and the Buffalo Bayou Partnership announced a restoration and adaptive reuse project that would turn the Sunset Coffee Building into a downtown cultural and entertainment destination. (For more information, see “Our Vision: Sunset Coffee Building”.)

Allen’s Landing, early 1900s. Sunset Coffee Building is left of center, in front of white building. Photo by Frank J. Schlueter. Courtesy Houston Public Library

For this puzzle we have a piece at the beginning (1910) and a piece at the end (2013), but what about the pieces in the middle? No doubt there are many, but Special Collections holds a significant one, which can be found in the Burdette Keeland Architectural Papers.

Burdette Keeland (UH 1950) was a prolific designer and an influential member of the UH Architecture faculty. To his students, he was cool. Joe Mashburn, later Dean of the College of Architecture, recalled, “I remember Burdette Keeland, Jr. emerging from his gray MG roadster and walking across that asphalt with his suit jacket over his shoulder and smoking a thin cigar. As students, we thought this was the way it should be for an architect – a cool sports car, a sleek Italian jacket. We wanted to be like him.” (“Burdette Keeland Jr. Remembered,” Cite 48 (Summer 2000), 9).

Burdette Keeland, Jr., late 1960s. Burdette Keeland Architectural Papers, UH Libraries, Special Collections (“Keeland Papers”).

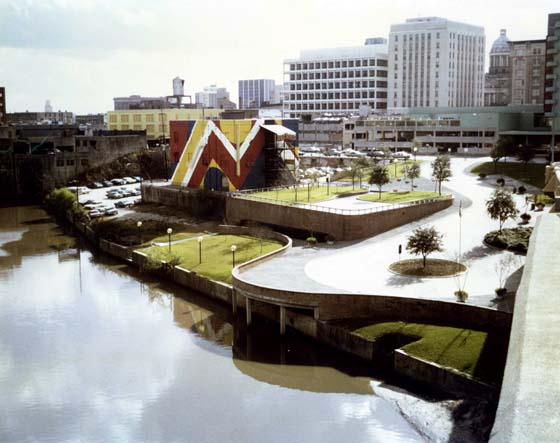

In the late 1960s the cool Mr. Keeland was part of a joint venture that bought what is now known as the Sunset Coffee Building with plans to develop it as an entertainment venue. Keeland acted as architect for the group and provided space for a restaurant and two nightclubs. To reach them, he added a three-story outdoor staircase, and in keeping with the spirit of the times, later painted the building in a wild psychedelic color scheme.

Love Street Light Circus and Feel Good Machine (c. 1967). Keeland Papers.

The top floor became home to the celebrated Love Street Light Circus and Feel Good Machine, run by artist David Adickes. From 1967 to 1970 Love Street hosted many of the top local bands of the day, such as the 13th Floor Elevators, Fever Tree, the Moving Sidewalks, and later, ZZ Top. Go-go dancers joined the bands onstage, while patrons lounged on the floor enjoying refreshments. (For more on Love Street, see “David Adickes – Love Street Light Circus and More” or “LOVE STREET LIGHT CIRCUS

AND FEELGOOD MACHINE!!!”)

Sunset Coffee Building with psychedelic paint scheme (c. 1971). Keeland Papers.

For a few years the building played an important role in Houston’s version of the “Summer of Love,” the heyday of the hippies and the counterculture movement. Popular with its patrons but unsuccessful as a business, Love Street closed in 1970. Keeland and his partners later sold the building. It was a short but colorful chapter in the life of this historic building. At Special Collections we have many such chapters, each waiting for researchers to fit them into their proper places in a larger historical puzzle.

Whether it’s a rare book printing found at long last or piece of ephemera found in an archival collection by chance, those who visit the University of Houston Special Collections almost always find something they cannot wait to share with others. Here we celebrate what makes the University of Houston Special Collections so special–our Favorite Things.

The satellite view is spectacular and confirms what we already know—Houston is big. At last count, Houston’s incorporated area covers about 667 square miles. We know this because the City of Houston Planning & Development Department has created an informative slide show that illustrates the city’s ever-changing boundaries. “Annexations in Houston or How we grew to 667 square miles in 175 years” can be found online.

If you want to research urban planning in Houston the old-fashioned way—using text and images printed on paper—try the Special Collections Department at UH Libraries. I recommend the old-fashioned way because, while it is not as convenient as surfing the web, it is way more fun.

Discoveries abound in Special Collections. Every folder holds a surprise. My most recent discovery was a set of maps from the Paddock Greater Houston Convention & Visitors Council Records. As the name suggests, this collection contains records collected by Marianita Paddock from her years with the Greater Houston Convention & Visitors Council. But it also includes maps of cities and counties in Texas from the mid-twentieth century. Some of the maps are common but others are unusual, such as a 1948 Ashburn’s Map of Houston in a special edition issued for Forest Park cemetery on Lawndale.

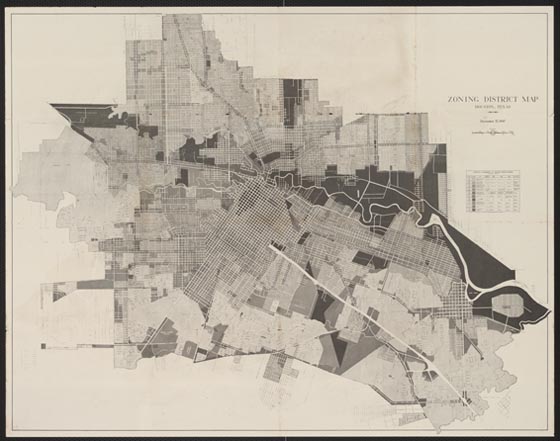

The most significant is the City of Houston’s Zoning District Map, December 15, 1947. Houston was small once, and I don’t mean when the Allen Brothers founded it in 1836. As late as the 1940s, it was a compact city of 75 square miles. This map reminds us that in 1947 the city’s boundaries extended no farther than Kirby Drive on the west, Brays Bayou on the southwest, and Sims Bayou on the southeast. The Heights, Rice Institute, and the new Texas Medical Center were on the edge of town.

City of Houston, Zoning District Map, December 15, 1947, Paddock Greater Houston Convention & Visitors Council Records

The map is a historical footnote to the larger question of urban planning in Houston. Most people know that Houston is the largest city in the country without land use zoning. So why was the city publishing a zoning map? The answer is that it was done to educate citizens about the issues in the upcoming special election in January 1948 when they would be asked to approve a new law authorizing zoning. It’s no spoiler to say that voters rejected the law. Progressives in Houston are gluttons for punishment and tried again in 1962 and 1993. Voters were unmoved and we still have no zoning.

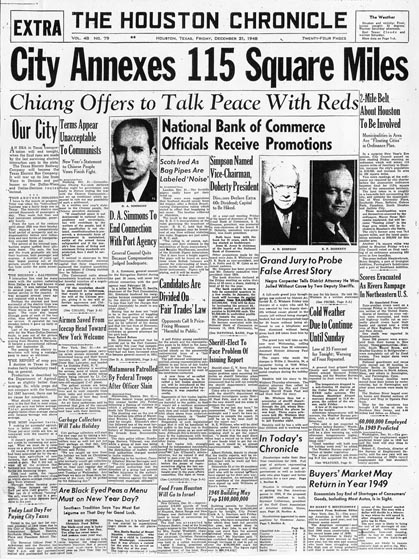

More importantly, the map is a detailed snapshot of the city’s boundaries, street system, and land uses on the eve of its great suburbanization. On December 31, 1948, only a year after the map was published, the city council approved an ordinance annexing a large swath of territory that more than doubled the city’s land area to 189 square miles. Houston was small no more. This was the first of many annexations, done to preserve the city’s tax base and its ability to grow.

City council waited until New Year’s Eve to drop this bombshell. The Houston Chronicle responded with a banner headline. Pasadena and other neighboring cities were not thrilled by the news. Their New Year’s hangover was beginning early and would continue for decades more.

Donald Barthelme, Adams Petroleum Center (c. 1955), aerial view of the proposed complex on Fannin at Brays Bayou. (Donald Barthelme Architectural Papers and Photographs)

The UH Digital Library recently announced its newest addition—the Donald Barthelme Sr. Architectural Papers and Photographs. The Digital Library makes accessible online important holdings of the University of Houston libraries and archives. These new items illustrate the work of noted architect Donald Barthelme through pencil sketches, photographs, and the detailed working drawings used to construct his buildings. They are only a small part of the total found in the Donald Barthelme Sr. Architectural Papers, but they illustrate his most important projects.

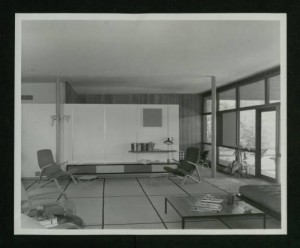

Barthelme Residence (c. 1952), living room looking east with parents’ bedroom in the background. (Donald Barthelme Sr. Architectural Papers and Photographs)

The earliest is Barthelme’s own residence (1939), a small flat-roof modernist house on Wynden Drive. The open plan created the illusion of a larger space within. A grid of Japanese tatami mats covering the floor met a similar grid of windows facing the patio. He filled the living room with iconic modernist furniture by Alvar Aalto, Charles Eames, and Eero Saarinen. In an unusual feature, the parents’ bedroom was open to the living room; a folding screen provided privacy from the children.

St. Rose of Lima Church and School won an award of merit from the American Institute of Architects in 1948 for its simple and austere brick forms. But Barthelme’s most important building was the award-winning West Columbia Elementary School,

Donald Barthelme, West Columbia Elementary School (1951), north court. (Donald Barthelme Architectural Papers and Photographs)

completed in 1951. Its innovative design departed from the traditional practice of placing classrooms along both sides of a long corridor. Instead, he arranged the building around two large courtyards; classrooms opened to the courts through floor-to-ceiling glass walls. The picture of a teacher and her students captures the cheerful atmosphere of Barthelme’s light-filled classrooms.

West Columbia Elementary School (1951), view of classroom with teacher and students. (Donald Barthelme Architectural Papers and Photographs)

In the mid-1950s, the Adams Petroleum Company hired Barthelme to design its new office building on Fannin Street. The company hoped to develop the large site as an office park, with the APC building to be followed by other office buildings. Barthelme spent hundreds of hours planning the large complex before Adams abandoned the scheme. The Digital Library contains a selection of rarely seen studies for this ambitious unbuilt project.

Through the UH Digital Library the public now has easy access to these images, some of which have never been published. As usual, the Donald Barthelme Sr. Architectural Papers are available to researchers at the UH Libraries’ Special Collections department.

M.D. Anderson Library has grown with the University of Houston, and its modest original building has been enlarged several times as needs have changed. Within these additions it is still possible to see evidence of the library’s 1970s master plan, only part of which was carried out.

At the building’s core is the original structure opened in 1950, a conservative modernist design by Staub and Rather. Clad in the white limestone of the university’s original buildings, the library harmonized with the nearby Ezekiel Cullen building without upstaging it. When the original library building, known today as the Red Wing, became inadequate, the university responded by adding a large eight-story tower (the Blue Wing), completed in 1968. Designed by Staub, Rather and Howze, the tower housed the research collections and study carrels necessary to support the university’s graduate degree programs.

This architect’s rendering shows the library’s original building (the Red Wing) in the foreground with the proposed tower (the Blue Wing) in the back. (UH Photographs Collection, University of Houston Buildings)

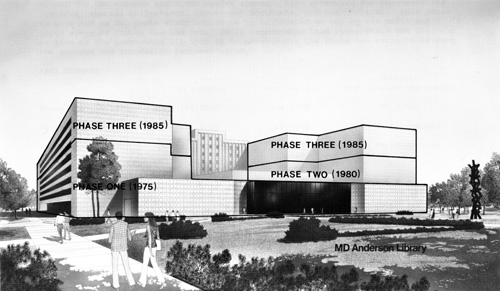

Despite this impressive addition, the university’s growth made further library expansion inevitable. In 1975 administrators retained Kenneth Bentsen (UH 1952), architect for Agnes Arnold Hall (1968) and Philip G. Hoffman Hall (1974), to prepare a master plan that would guide this expansion. Bentsen proposed to enlarge the library’s main building substantially in three phases over a ten-year period. The first phase would include a five-story wing on the north side of the building and a new black-glass façade that would house a lobby and lounge area. This addition (the Brown Wing) was completed in 1978 according to Bentsen’s design.

Phase Two would add a matching five-story wing on the south side. When more space was needed, a third phase would add two more floors to the north and south wings. Bentsen projected that this three-stage expansion might be completed by the end of the 1980s.

Kenneth Bentsen’s 1975 master plan proposed to expand the M.D. Anderson library building in three phases. (Kenneth E. Bentsen Architectural Papers)

That decade brought a major recession in the energy industry, which devastated the Texas economy. State government funding for building projects dried up, and the university was unable to continue with the proposed library additions.

When planning for a major library expansion resumed in the late 1990s, the architects Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott followed Bentsen’s general idea for a large wing on the south side while renovating the main entrance with a new façade inspired by the Ezekiel Cullen building. The library’s 1975 master plan has been forgotten, but some of its ideas lived on.

M.D. Anderson Library as it appears today, with most recent additions by Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson and Abbott (2005). (Photo by the author)

The Kenneth E. Bentsen Architectural Papers are housed in the library’s Special Collections Department and are currently being processed. Pictures of the M.D. Anderson Library and other campus buildings are available in the University of Houston Buildings Collection of the UH Digital Library.