Beverly Murphy was elected as the first African-American President of the Medical Library Association in 2018.

Murphy is the Assistant Director of Communications and Web Content, as well as the nursing liaison, at the Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives. She was recruited to a technical services position directly out of library school, and has been a leader in health sciences libraries ever since. In addition to breaking barriers as the first African-American President of the Medical Library Association, she was also the first African-American chair of the Mid-Atlantic Chapter of the Medical Library Association, the first African-American editor of MLA News, and the first African-American Recipient of the Marcia C. Noyes Award.

Murphy is the Assistant Director of Communications and Web Content, as well as the nursing liaison, at the Duke University Medical Center Library & Archives. She was recruited to a technical services position directly out of library school, and has been a leader in health sciences libraries ever since. In addition to breaking barriers as the first African-American President of the Medical Library Association, she was also the first African-American chair of the Mid-Atlantic Chapter of the Medical Library Association, the first African-American editor of MLA News, and the first African-American Recipient of the Marcia C. Noyes Award.

When asked about her advice for new leaders, Murphy said, “I believe you first have to learn to follow before you can lead. Don’t be afraid to take risks but listen and learn from every angle and expect the unexpected. You don’t have to be at the top of the food chain to be an effective leader, but you should be at the top of your game to effect change. Learn everything you can about leadership principles and apply them when given the right circumstances. Be an example people want to follow, engage those around you, and help them shine. Be accountable, honest, and transparent.”

Source: https://www.mlanet.org/blog/i-am-mla-beverly-murphy-ahip-fmla

In 1998, Dr. Lisa I. Iezzoni became the first woman appointed professor in the department of medicine at Beth Israel Hospital. Throughout much of her career, she has focused her research agenda on the health concerns of people living with disabilities.

Iezzoni earned a master’s degree in health policy from the Harvard School of Public Health in the 1970s, and went on to receive her medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1984. During her first year of medical school, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS). Because of the lack of accommodations available at the time for people with disabilities, as well as the lack of acceptance within medicine, she opted to follow a research track rather than complete an internship and become licensed as a medical doctor.

Iezzoni earned a master’s degree in health policy from the Harvard School of Public Health in the 1970s, and went on to receive her medical degree from Harvard Medical School in 1984. During her first year of medical school, she was diagnosed with multiple sclerosis (MS). Because of the lack of accommodations available at the time for people with disabilities, as well as the lack of acceptance within medicine, she opted to follow a research track rather than complete an internship and become licensed as a medical doctor.

With her background in health policy, this was a natural fit. Her research has largely focused on measuring quality of care and improving fairness of payment. Additionally, she has researched disability, including health policy issues, health disparities, and the implications of disabling conditions on daily life.

In recent years, she has gotten involved in the #DocsWithDisabilities movement, calling for the profession to be more open and less ableist in order to improve healthcare.

Info and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_161.html

Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte was a doctor, public health advocate, and social reformer widely recognized as the first Indigenous woman to obtain a medical degree in the U.S. Dr. La Flesche Picotte was born in the Omaha reservation in 1865, the youngest daughter of Joseph La Flesche, the last recognized Chief of the Omaha tribe.

During her studies at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMPC), Dr. La Flesche Picotte was sponsored by the Connecticut Indian Association (CIA) throughout her medical program and overcame societal and racial discrimination to become valedictorian, graduating at the top of her class in 1889.

During her studies at the Women’s Medical College of Pennsylvania (WMPC), Dr. La Flesche Picotte was sponsored by the Connecticut Indian Association (CIA) throughout her medical program and overcame societal and racial discrimination to become valedictorian, graduating at the top of her class in 1889.

Throughout her career, Dr. La Flesche Picotte worked for the Office of Indian Affairs (1889-1983) as the physician for the boarding school, was an active community advocate, and traveled in and around the reservation making house calls for community members.

She was an active social reformer and public health advocate, strongly in favor of temperance and even advocated for a prohibition law that would impact the Omaha tribe. Dr. La Flesche Picotte was a proponent of preventive care and worked on educating her community on hygiene and food sanitation, both for general health and to help prevent the spread of tuberculosis. She also helped tribal members with inheritance issues they experienced, specifically with regard to land sales.

Dr. La Flesche Picotte went on to establish the Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte Memorial Hospital, the first privately-funded hospital on the Omaha reservation that went on to serve the tribal community until the 1940s. Today, the building stands as a National Historic Landmark and serves as a reminder of the amazing work of Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte.

Info source: The Incredible Legacy of Susan La Flesche, the First Native American to Earn a Medical Degree, Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte, Susan La Flesche Picotte, and Susan La Flesche Picotte, M.D.: Omaha Indian leader and reformer.

Photo source: Dr. Susan La Flesche Picotte

In 1967, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright became the highest-ranking African American woman at a nationally recognized medical institution when she was named an Associate Dean at New York Medical College. She was also the first woman to be elected as president of the New York Cancer Society.

Jane Cooke Wright was born in New York in 1919, the daughter of Dr. Louis Wright, one of the first African Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School.

Jane Cooke Wright was born in New York in 1919, the daughter of Dr. Louis Wright, one of the first African Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School.

After graduating with honors from New York Medical College in 1945, she interned at Bellevue Hospital and completed a residency at Harlem Hospital.

The majority of her career was spent in oncology as a leader in chemotherapy research. In 1964, she was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. Three years later, she returned to her alma mater as a leader, becoming a professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and Associate Dean.

Dr. Wright retired in 1987 after a long and productive career and passed away in 2013.

Information and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_336.html/

Mary Eliza Mahoney was the first African American woman to complete nurse’s training in the United States, and an active organizer among African American nurses.

Born in Boston in 1845 to freed slaves, Mahoney knew early on that she wanted to become a nurse; however, Black women in the 19th century often had a difficult time becoming trained and licensed nurses. Nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women, whereas in the North, though the opportunity was still severely limited, African Americans had a greater chance at acceptance into training and graduate programs.

Born in Boston in 1845 to freed slaves, Mahoney knew early on that she wanted to become a nurse; however, Black women in the 19th century often had a difficult time becoming trained and licensed nurses. Nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women, whereas in the North, though the opportunity was still severely limited, African Americans had a greater chance at acceptance into training and graduate programs.

At the age of 18, she decided to pursue a career in nursing, working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. The NEHWC became the first institution to offer a program allowing women to work towards entering the healthcare industry, which was predominantly led by men. Despite the NEHWC’s progressiveness, Mahoney worked there as a cook, maid, and washerwoman for 15 years before she was admitted as a student.

In 1878, at age 33, she was accepted in that hospital’s nursing school, the first professional nursing program in the country. Mahoney graduated in 1879 as a registered nurse. Out of a class of 42 students, she and three white women were the only ones to receive their degree – the first Black woman to do so in the United States.

After receiving her nursing diploma, Mahoney worked for many years as a private care nurse, earning a distinguished reputation. She worked for predominantly white, wealthy families and the majority of her work was with new mothers and newborns. Families who employed Mahoney praised her efficiency in her nursing profession. Mahoney’s professionalism helped raise the status and standards of all nurses, especially minorities. During the early years of her employment, African American nurses were often treated as if they were household servants rather than professionals. Mahoney refused to take her meals with household staff to further dismiss the relation between the professions. As Mahoney’s reputation quickly spread, she received private-duty nursing requests from patients in states in the north and along the south east coast.

In 1896 Mahoney became one of the first black members of the organization that later became the American Nurses Association (ANA). When that later organization proved slow to admit black nurses, Mahoney strongly supported the establishment of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (N.A.C.G.N.), and delivered the welcome address at that organization’s first annual convention, in 1909. In her speech, she recognized the inequalities in her nursing education, and in nursing education of the day. The NACGN members gave Mahoney a lifetime membership in the association and a position as the organization’s chaplain.

In retirement, Mahoney was still concerned was deeply concerned with women’s equality and a strong supporter of the movement to gain women the right to vote. When that movement succeeded with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, she was among the first women in Boston to register to vote — at the age of 76.

Mahoney contracted breast cancer in 1923 and died in 1926. In 1936, the N.A.C.G.N. established an award in her honor (later continued by the A.N.A.) to raise the status of black nurses. She was inducted into the A.N.A.’s Hall of Fame in 1976.

Information and photo sources:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-mahoney

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/partners-african-american-medical-pioneers/

We will be continuing our #DiversityInHealthcare series in 2021 with monthly posts.

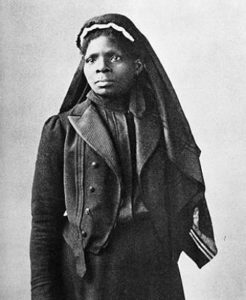

Susie King Taylor is recognized as the first African American Army nurse.

Taylor was born into slavery in 1848 Georgia. She attended two clandestine schools in order to learn to read and write as a child. At the age of 14, she joined the US Army’s first black regiment, initially as a laundress. Her accomplishments soon became apparent, however, and she quickly moved on to other responsibilities, including serving as a nurse and a teacher. She taught many of the soldiers, who were former slaves, how to read.

While history has often omitted the contributions of Black Americans in the Civil War, we are fortunate to have more detailed information on Susie King Taylor. This is because she wrote and published a memoir about her experiences in 1902 entitled Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers.

Info sources: https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm; https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=5be2377c246c4b5483e32ddd51d32dc0

Photo source: Library of Congress via https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm

Julia Pearl Hughes was a trailblazer in pharmacy, believed to be one of the first African-American hospital pharmacists and the first African-American woman to own and operate a drugstore.

Dr. Hughes graduated from Howard University with a pharmaceutical degree in 1897. After completing postgraduate work, she ran the hospital pharmacy at Frederick Douglass Hospital. In 1900, she opened the Hughes Pharmacy drugstore in Philadelphia.

Dr. Hughes graduated from Howard University with a pharmaceutical degree in 1897. After completing postgraduate work, she ran the hospital pharmacy at Frederick Douglass Hospital. In 1900, she opened the Hughes Pharmacy drugstore in Philadelphia.

In addition to her achievements in pharmacy, Dr. Hughes had a number of other successful pursuits. These included founding a haircare company and a newspaper, successfully suing a railroad for racial discrimination, and running for office in the New York State Assembly.

Info and photo source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hughes-julia-pearl-1873-1950/

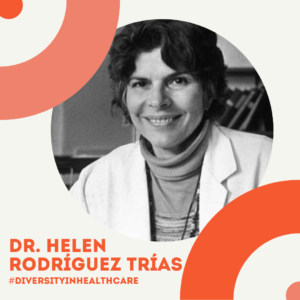

Helen Rodríguez Trías was a pediatrician, educator and women’s rights activist. She was the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association (APHA), a founding member of the Women’s Caucus of the APHA, and a recipient of the Presidential Citizens Medal. She is credited with helping to expand the range of public health services for women and children in minority and low-income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Born in New York in 1929, Helen Rodríguez spent her early years in Puerto Rico, returning to New York with her family when she was 10. Growing up as a Puerto Rican in New York City, she experienced racism and discrimination first-hand. Rodriguez-Trias earned her BA degree from the University of Puerto Rico in 1957 where she became a student activist on issues such as freedom of speech and Puerto Rican independence. She then entered the University of Puerto Rico’s school of medicine and obtained her medical degree in 1960. Rodriguez-Trias chose medicine because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people”

Born in New York in 1929, Helen Rodríguez spent her early years in Puerto Rico, returning to New York with her family when she was 10. Growing up as a Puerto Rican in New York City, she experienced racism and discrimination first-hand. Rodriguez-Trias earned her BA degree from the University of Puerto Rico in 1957 where she became a student activist on issues such as freedom of speech and Puerto Rican independence. She then entered the University of Puerto Rico’s school of medicine and obtained her medical degree in 1960. Rodriguez-Trias chose medicine because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people”

During her residency at the University Hospital in San Juan, she established the first center for the care of newborn babies in Puerto Rico. Under her direction, the hospital’s death rate for newborns decreased 50 percent within three years.

When she returned to New York in 1970, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias decided to work in community medicine. After attending a conference on abortion at Barnard College in 1970, she focused on reproductive rights. Throughout the 1970s, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias was an active member of the women’s health movement. She was inspired by “the experiences of my own mother, my aunts and sisters, who faced so many restraints in their struggle to flower and reach their own potential.”

Rodriguez-Trias joined the effort to stop sterilization abuse. Poor women, women of color, and women with physical disabilities were far more likely to be sterilized than white, middle-class women. Rodriguez-Trias was a founding member of both the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse and the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, and testified before the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for passage of federal sterilization guidelines in 1979. The guidelines, which she helped draft, require a woman’s written consent to sterilization, offered in a language they can understand, and set a waiting period between the consent and the sterilization procedure.

Rodriguez-Trias was also a founding member of both the Women’s Caucus and the Hispanic Caucus of the American Public Health Association and the first Latina to serve as president. Toward the end of her life she said, “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life…Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment…it’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.”

In January 2001 she received a Presidential Citizen’s Medal for her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV and AIDS, and the poor. Helen Rodriguez-Trias died of complications from cancer in December, 2001.

Information and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_273.html

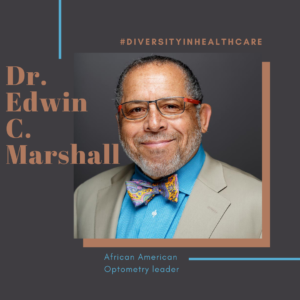

Edwin C. Marshall, O.D., M.S., M.P.H. is a Professor Emeritus with the Indiana University School of Optometry. Prior to retirement, he worked as IU’s vice president for Diversity, Equity and Multicultural Affairs.

During his career at IU, he launched the Indiana University Summer Institute in Health Related Professions, which helped get minority students into health professions, including optometry. He also worked to establish IU’s first satellite clinic in an underserved area, providing access to care and teaching students to provide a high level of care to all patients.

Dr. Marshall has a distinguished record of service which includes previously serving as president of the National Optometric Association, the Indiana Optometric Association, and the Indiana Public Health Association.

He was inducted into the National Optometry Hall of Fame in 2009. This prestigious group only includes 84 members as of 2020.

Information sources: https://optometry.iu.edu/people-directory/marshall-edwin.html; https://www.facebook.com/NatOptAssoc/posts/i-was-the-first-african-american-male-matriculated-into-indiana-universitys-scoo/10156230081023963/

Photo source: https://optometry.iu.edu/people-directory/marshall-edwin.html

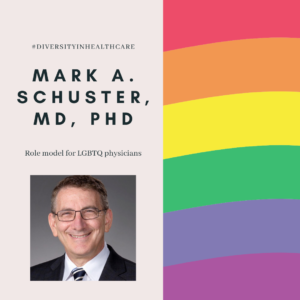

Mark A. Schuster, MD, PhD is the founding dean and CEO of the Kaiser Permanente Bernard J. Tyson School of Medicine. In 2010, he gave a speech on being a gay physician. His talk struck a chord with many and was published and covered widely in the media, serving as an inspiration for LGBTQ physicians and medical students.

Dr. Schuster earned his undergraduate degree from Yale and his medical degree from Harvard in 1987. Throughout his education and career, he felt pressure to hide his sexual orientation in order to be successful. He was unwilling to bow to this pressure, however, and has been an unwavering advocate for fair treatment of LGBTQ clinicians and patients.

Dr. Schuster earned his undergraduate degree from Yale and his medical degree from Harvard in 1987. Throughout his education and career, he felt pressure to hide his sexual orientation in order to be successful. He was unwilling to bow to this pressure, however, and has been an unwavering advocate for fair treatment of LGBTQ clinicians and patients.

He is an international leader in child, adolescent, and family health, having researched and written extensively on these topics. He is an elected member of the National Academy of Medicine, and is currently leading the new medical school at Kaiser Permanente.

Info sources: https://hms.harvard.edu/news/doctor-out; https://medschool.kp.org/about/board-of-directors/mark-a-schuster

Photo source: https://medschool.kp.org/content/dam/internet/kp/som/homepage/about/leadership/mark_schuster_960x960.jpg