Jerome M. Adams served as the 20th Surgeon General of the United States from 2017 – 2021.

Dr. Adams earned his master of public health degree from the University of California at Berkeley, and his medical degree from Indiana University School of Medicine. He has completed residencies in both internal medicine and anesthesiology, and is a board certified anesthesiologist.

After time in private practice and serving on the faculty of Indiana University School of Medicine, Dr. Adams was appointed as Indiana State Health Commissioner. While in that position, he headed the state’s response to an unprecedented HIV outbreak.

After time in private practice and serving on the faculty of Indiana University School of Medicine, Dr. Adams was appointed as Indiana State Health Commissioner. While in that position, he headed the state’s response to an unprecedented HIV outbreak.

As Surgeon General, he oversaw the U.S. Public Health Service Commissioned Corps in order to promote and advance health. While in office, he focused on addressing the opioid epidemic as well as the COVID-19 pandemic.

He continues to be heavily involved in promoting health information to the public via traditional media outlets as well as on Twitter, where he has more than 56,000 followers.

UH librarians Rachel and Stefanie had the opportunity to see him speak in 2018, and the photo shared here was taken by Rachel at that event.

Info source: https://www.hsph.harvard.edu/voices/events/jerome-adams-20th-surgeon-general-of-the-united-states/

Ernest Grant is the 36th president of the American Nurses Association (ANA), and the first man to hold that position.

Dr. Grant has worked as a nurse for more than 30 years. He earned his BSN from North Carolina Central University and his MSN and PhD both from University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He specializes in burn care and fire safety, fields in which he is an internationally recognized expert. He has led burn outreach at the North Carolina Jaycee Burn Center, as well as with the U.S. military. He received a Nurse of the Year Award from President George W. Bush in 2002 in honor of his work with World Trade Center burn victims.

Dr. Grant has worked as a nurse for more than 30 years. He earned his BSN from North Carolina Central University and his MSN and PhD both from University of North Carolina at Greensboro. He specializes in burn care and fire safety, fields in which he is an internationally recognized expert. He has led burn outreach at the North Carolina Jaycee Burn Center, as well as with the U.S. military. He received a Nurse of the Year Award from President George W. Bush in 2002 in honor of his work with World Trade Center burn victims.

Additionally, Dr. Grant has a strong record of professional service. He also continues to serve as adjunct faculty for the UNC-Chapel Hill of Nursing, where he passes his expertise on to student nurses.

Dr. Grant began his term as ANA president in 2018. Throughout the COVID-19 pandemic, he has advocated for nurse safety and worked to prevent vaccine hesitancy, particularly in the African-American community.

Info and photo source: https://www.nursingworld.org/ana/leadership-and-governance/board-of-directors/ana-president/

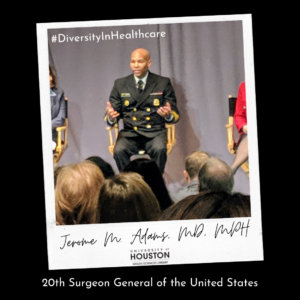

Dr. Eliza Lo Chin is the author of the 2002 book This Side of Doctoring: Reflections From Women in Medicine. The book is a collection of the experiences of women physicians. After dealing with struggles in her own life around being a young physician, wife, and mother, she recognized a larger need and completed this project to help fill the mentoring void for women trying to balance family and career.

Dr. Chin completed her undergraduate studies at UC Berkeley, graduated from Harvard Medical School, and was a resident with the Primary Care Program at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She has an interest in women’s health, and served as the course director for Columbia University’s Women’s Health Elective. She is currently the Executive Director of the American Medical Women’s Association and Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine at UC San Francisco. She continues to give back by mentoring young women in medicine.

Dr. Chin completed her undergraduate studies at UC Berkeley, graduated from Harvard Medical School, and was a resident with the Primary Care Program at Boston’s Brigham and Women’s Hospital. She has an interest in women’s health, and served as the course director for Columbia University’s Women’s Health Elective. She is currently the Executive Director of the American Medical Women’s Association and Assistant Clinical Professor of Medicine at UC San Francisco. She continues to give back by mentoring young women in medicine.

Information and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_60.html; Information source: https://www.amwa-doc.org/amwa103/eliza-lo-chin/

Elizabeth Fee, PhD, was an influential historian of science, medicine, and public health.

Dr. Fee began teaching at the State University of New York at Binghamton and was extremely popular as a scholar of science and medical history, as well as new and controversial courses in human sexuality.

From 1974 to 1995, Dr. Fee was a professor at the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health (now Bloomberg School). She worked in departments including health humanities, international health, and health policy. During her tenure at Johns Hopkins, Dr. Fee wrote a history of the School of Public Health, Disease and Discovery: A History of the Johns Hopkins School of Hygiene and Public Health, 1916–1939. This is considered the first “biography” of the first school of public health, and it documented power networks in a supposedly technocratic field.

Baltimore is also where Dr. Fee met and fell in love with her lifetime partner and wife, Mary Garafolo, an artist and a nurse. They married in Vancouver, Canada, in 2005.

Dr. Fee joined the National Library of Medicine (NLM) from 1995 to 2018 as Chief of the NLM History of Medicine Division. She oversaw moves to restructure the organization around three sections: Rare Books and Early Manuscripts, Images and Archives, and Exhibitions. She was appointed Chief Historian of the National Library of Medicine in 2011.

Over the course of her entire career, Dr. Fee authored, co-authored, edited, or co-edited nearly thirty scholarly books and hundreds of articles, on topics as varied as the racialized treatment of syphilis, the history of the toothbrush, and bioterrorism. She became particularly well known for her work to document and analyze the history of HIV/AIDS. Dr. Fee coedited two groundbreaking volumes on AIDS, as it was becoming a global modern plague: AIDS: The Burden of History (1988) and AIDS: The Making of a Chronic Disease (1992). Her work informed scholarship on lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and queer health and wellbeing.

Shortly before her death Dr. Fee retired to become an independent researcher in 2018. She died from complications of amyotrophic lateral sclerosis (ASL) in October 2018.

Info sources: Elizabeth Fee (The Lancet), Elizabeth Fee (1946-2018) (AJPH), and NLM Mourns the Loss of Elizabeth Fee, PhD, former Chief of the NLM History of Medicine Division (NLM).

Photo source: The Lancet via: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32832-0

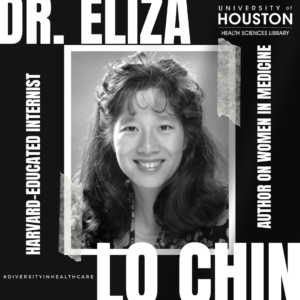

In 1967, Dr. Jane Cooke Wright became the highest-ranking African American woman at a nationally recognized medical institution when she was named an Associate Dean at New York Medical College. She was also the first woman to be elected as president of the New York Cancer Society.

Jane Cooke Wright was born in New York in 1919, the daughter of Dr. Louis Wright, one of the first African Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School.

Jane Cooke Wright was born in New York in 1919, the daughter of Dr. Louis Wright, one of the first African Americans to graduate from Harvard Medical School.

After graduating with honors from New York Medical College in 1945, she interned at Bellevue Hospital and completed a residency at Harlem Hospital.

The majority of her career was spent in oncology as a leader in chemotherapy research. In 1964, she was appointed by President Lyndon B. Johnson to the President’s Commission on Heart Disease, Cancer, and Stroke. Three years later, she returned to her alma mater as a leader, becoming a professor of surgery, head of the Cancer Chemotherapy Department, and Associate Dean.

Dr. Wright retired in 1987 after a long and productive career and passed away in 2013.

Information and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_336.html/

Mary Eliza Mahoney was the first African American woman to complete nurse’s training in the United States, and an active organizer among African American nurses.

Born in Boston in 1845 to freed slaves, Mahoney knew early on that she wanted to become a nurse; however, Black women in the 19th century often had a difficult time becoming trained and licensed nurses. Nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women, whereas in the North, though the opportunity was still severely limited, African Americans had a greater chance at acceptance into training and graduate programs.

Born in Boston in 1845 to freed slaves, Mahoney knew early on that she wanted to become a nurse; however, Black women in the 19th century often had a difficult time becoming trained and licensed nurses. Nursing schools in the South rejected applications from African American women, whereas in the North, though the opportunity was still severely limited, African Americans had a greater chance at acceptance into training and graduate programs.

At the age of 18, she decided to pursue a career in nursing, working at the New England Hospital for Women and Children. The NEHWC became the first institution to offer a program allowing women to work towards entering the healthcare industry, which was predominantly led by men. Despite the NEHWC’s progressiveness, Mahoney worked there as a cook, maid, and washerwoman for 15 years before she was admitted as a student.

In 1878, at age 33, she was accepted in that hospital’s nursing school, the first professional nursing program in the country. Mahoney graduated in 1879 as a registered nurse. Out of a class of 42 students, she and three white women were the only ones to receive their degree – the first Black woman to do so in the United States.

After receiving her nursing diploma, Mahoney worked for many years as a private care nurse, earning a distinguished reputation. She worked for predominantly white, wealthy families and the majority of her work was with new mothers and newborns. Families who employed Mahoney praised her efficiency in her nursing profession. Mahoney’s professionalism helped raise the status and standards of all nurses, especially minorities. During the early years of her employment, African American nurses were often treated as if they were household servants rather than professionals. Mahoney refused to take her meals with household staff to further dismiss the relation between the professions. As Mahoney’s reputation quickly spread, she received private-duty nursing requests from patients in states in the north and along the south east coast.

In 1896 Mahoney became one of the first black members of the organization that later became the American Nurses Association (ANA). When that later organization proved slow to admit black nurses, Mahoney strongly supported the establishment of the National Association of Colored Graduate Nurses (N.A.C.G.N.), and delivered the welcome address at that organization’s first annual convention, in 1909. In her speech, she recognized the inequalities in her nursing education, and in nursing education of the day. The NACGN members gave Mahoney a lifetime membership in the association and a position as the organization’s chaplain.

In retirement, Mahoney was still concerned was deeply concerned with women’s equality and a strong supporter of the movement to gain women the right to vote. When that movement succeeded with the passage of the Nineteenth Amendment in 1920, she was among the first women in Boston to register to vote — at the age of 76.

Mahoney contracted breast cancer in 1923 and died in 1926. In 1936, the N.A.C.G.N. established an award in her honor (later continued by the A.N.A.) to raise the status of black nurses. She was inducted into the A.N.A.’s Hall of Fame in 1976.

Information and photo sources:

https://www.womenshistory.org/education-resources/biographies/mary-mahoney

https://www.pbs.org/wgbh/americanexperience/features/partners-african-american-medical-pioneers/

We will be continuing our #DiversityInHealthcare series in 2021 with monthly posts.

Susie King Taylor is recognized as the first African American Army nurse.

Taylor was born into slavery in 1848 Georgia. She attended two clandestine schools in order to learn to read and write as a child. At the age of 14, she joined the US Army’s first black regiment, initially as a laundress. Her accomplishments soon became apparent, however, and she quickly moved on to other responsibilities, including serving as a nurse and a teacher. She taught many of the soldiers, who were former slaves, how to read.

While history has often omitted the contributions of Black Americans in the Civil War, we are fortunate to have more detailed information on Susie King Taylor. This is because she wrote and published a memoir about her experiences in 1902 entitled Reminiscences of My Life in Camp with the 33d United States Colored Troops, Late 1st S.C. Volunteers.

Info sources: https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm; https://www.loc.gov/ghe/cascade/index.html?appid=5be2377c246c4b5483e32ddd51d32dc0

Photo source: Library of Congress via https://www.nps.gov/people/susie-king-taylor.htm

Julia Pearl Hughes was a trailblazer in pharmacy, believed to be one of the first African-American hospital pharmacists and the first African-American woman to own and operate a drugstore.

Dr. Hughes graduated from Howard University with a pharmaceutical degree in 1897. After completing postgraduate work, she ran the hospital pharmacy at Frederick Douglass Hospital. In 1900, she opened the Hughes Pharmacy drugstore in Philadelphia.

Dr. Hughes graduated from Howard University with a pharmaceutical degree in 1897. After completing postgraduate work, she ran the hospital pharmacy at Frederick Douglass Hospital. In 1900, she opened the Hughes Pharmacy drugstore in Philadelphia.

In addition to her achievements in pharmacy, Dr. Hughes had a number of other successful pursuits. These included founding a haircare company and a newspaper, successfully suing a railroad for racial discrimination, and running for office in the New York State Assembly.

Info and photo source: https://www.blackpast.org/african-american-history/hughes-julia-pearl-1873-1950/

Helen Rodríguez Trías was a pediatrician, educator and women’s rights activist. She was the first Latina president of the American Public Health Association (APHA), a founding member of the Women’s Caucus of the APHA, and a recipient of the Presidential Citizens Medal. She is credited with helping to expand the range of public health services for women and children in minority and low-income populations in the United States, Central and South America, Africa, Asia, and the Middle East.

Born in New York in 1929, Helen Rodríguez spent her early years in Puerto Rico, returning to New York with her family when she was 10. Growing up as a Puerto Rican in New York City, she experienced racism and discrimination first-hand. Rodriguez-Trias earned her BA degree from the University of Puerto Rico in 1957 where she became a student activist on issues such as freedom of speech and Puerto Rican independence. She then entered the University of Puerto Rico’s school of medicine and obtained her medical degree in 1960. Rodriguez-Trias chose medicine because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people”

Born in New York in 1929, Helen Rodríguez spent her early years in Puerto Rico, returning to New York with her family when she was 10. Growing up as a Puerto Rican in New York City, she experienced racism and discrimination first-hand. Rodriguez-Trias earned her BA degree from the University of Puerto Rico in 1957 where she became a student activist on issues such as freedom of speech and Puerto Rican independence. She then entered the University of Puerto Rico’s school of medicine and obtained her medical degree in 1960. Rodriguez-Trias chose medicine because it “combined the things I loved the most, science and people”

During her residency at the University Hospital in San Juan, she established the first center for the care of newborn babies in Puerto Rico. Under her direction, the hospital’s death rate for newborns decreased 50 percent within three years.

When she returned to New York in 1970, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias decided to work in community medicine. After attending a conference on abortion at Barnard College in 1970, she focused on reproductive rights. Throughout the 1970s, Dr. Rodriguez-Trias was an active member of the women’s health movement. She was inspired by “the experiences of my own mother, my aunts and sisters, who faced so many restraints in their struggle to flower and reach their own potential.”

Rodriguez-Trias joined the effort to stop sterilization abuse. Poor women, women of color, and women with physical disabilities were far more likely to be sterilized than white, middle-class women. Rodriguez-Trias was a founding member of both the Committee to End Sterilization Abuse and the Committee for Abortion Rights and Against Sterilization Abuse, and testified before the Department of Health, Education, and Welfare for passage of federal sterilization guidelines in 1979. The guidelines, which she helped draft, require a woman’s written consent to sterilization, offered in a language they can understand, and set a waiting period between the consent and the sterilization procedure.

Rodriguez-Trias was also a founding member of both the Women’s Caucus and the Hispanic Caucus of the American Public Health Association and the first Latina to serve as president. Toward the end of her life she said, “I hope I’ll see in my lifetime a growing realization that we are one world. And that no one is going to have quality of life unless we support everyone’s quality of life…Not on a basis of do-goodism, but because of a real commitment…it’s our collective and personal health that’s at stake.”

In January 2001 she received a Presidential Citizen’s Medal for her work on behalf of women, children, people with HIV and AIDS, and the poor. Helen Rodriguez-Trias died of complications from cancer in December, 2001.

Information and photo source: https://cfmedicine.nlm.nih.gov/physicians/biography_273.html

Edwin C. Marshall, O.D., M.S., M.P.H. is a Professor Emeritus with the Indiana University School of Optometry. Prior to retirement, he worked as IU’s vice president for Diversity, Equity and Multicultural Affairs.

During his career at IU, he launched the Indiana University Summer Institute in Health Related Professions, which helped get minority students into health professions, including optometry. He also worked to establish IU’s first satellite clinic in an underserved area, providing access to care and teaching students to provide a high level of care to all patients.

Dr. Marshall has a distinguished record of service which includes previously serving as president of the National Optometric Association, the Indiana Optometric Association, and the Indiana Public Health Association.

He was inducted into the National Optometry Hall of Fame in 2009. This prestigious group only includes 84 members as of 2020.

Information sources: https://optometry.iu.edu/people-directory/marshall-edwin.html; https://www.facebook.com/NatOptAssoc/posts/i-was-the-first-african-american-male-matriculated-into-indiana-universitys-scoo/10156230081023963/

Photo source: https://optometry.iu.edu/people-directory/marshall-edwin.html