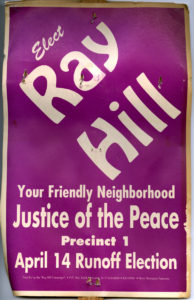

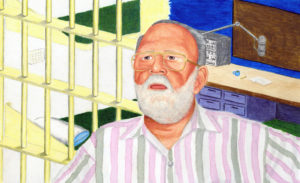

Detail from a painting of Ray Hill, from the Ray Hill Papers

Timing and happenstance played a large role in the personal papers of Ray Hill coming to the University of Houston. What started over a year and half ago, first through a visit by documentary filmmakers to UH Special Collections looking for footage on Houston’s LGBT Community during the 1970s, led not only to an introduction to Ray Hill, but developed into several subsequent conversations and meetings with Ray over coffee at the local Montrose Starbucks in Hawthorne Square. Ray held us as a captive audience, regaling us with stories of his time in prison for burglary, to his release and work in Houston’s LGBT community, to meeting and going toe to toe with the legendary Harvey Milk, and most importantly his Prison Show on KPFT. As he would describe it, the Prison Show served as a lifeline to prisoners, connecting them to their families and the outside world that no prison wall could keep out.

He was a master at holding court and was never short of words, wit, humor, and wisdom given at the right moments. “Ray Hill, Citizen Provocateur,” as listed on his business card, was a self described writer, activist, actor, and raconteur to name but a few of the titles to which he laid claim. Ray was not someone to meet, but someone to experience. A force of nature and larger than life, he was completely at home whether talking with political dignitaries on issues concerning prison reform or to members of the LGBT community seeking him for counsel and personal advice. Ray’s genius and brilliance were not in the telling of the truth, but in the telling and retelling of the story that made you believe, or at least made you think.

For a man like Ray Hill, who fought against the system for so long, one might think it ironic that he would place his personal archives with the University of Houston Libraries Special Collections. It made sense when we spoke to Ray on the significance UH libraries had on his life and how it shaped his formative years. As Ray would tell it, even before he was old enough to be a university student, he would sneak into the library stacks to find books that helped him discover or understand himself as a gay man. Placing his personal archives at UH, he is contributing to that exploration and understanding for current and future generations of students. Ray’s papers are now a major part of the Libraries’ significant LGBT historical collections alongside the Annise Parker Papers, the Gulf Coast Archive & Museum of GLBT History collection, the Diana Foundation Records, and many others. It is really an honor for us that Ray entrusted UH Libraries to preserve his history and make it accessible to our campus and our community.

The Ray Hill Papers collection contains 62 boxes of correspondence, awards, organization documents, photographs, audio/video recordings, publications, and artifacts that document Ray’s life and work as an LGBT community activist and prisoners’ rights reformer. His archives document the various aspects and endeavors of a complex individual whose work has affected so many in the community and beyond, capturing a life well-lived.

Last month Lawndale Art Center hosted the 15th annual Zine Fest Houston festival. Held annually in Houston, Texas, Zine Fest Houston (ZFH) was founded in 2004 by local creative shane patrick boyle as an event dedicated to promoting zines, mini-comics, and other forms of small press, alternative, underground, DIY media and art. Following the donation of the ZFH records and zine collections to UH’s Special Collections and the in the wake of boyle’s unexpected passing in 2017, current ZFH organizers (Maria-Elisa Heg and Stacy Kirages) collaboratively worked with UH’s Hispanic Collections Archivist, Elizabeth Lisa Cruces to increase awareness of boyle’s contributions to Houston’s DIY community and local history. boyle was an avid collector and creator of zines and is responsible for the bulk of zines and ephemera found in the collection. Thanks to spb’s collecting and contributions to growing the DIY scene in Houston, ZFH and other creatives have been able to flourish.

In addition to showcasing some of the earliest hand-made artwork and ephemera from the ZFH Records, Cruces provided information to attendees on how to make their own zines and how to donate zines to the archives. Regarding the future of this living archive, Cruces said, “For the ZFH archives to succeed in their mission—to more inclusively preserve Houston’s diverse voices, in particular LGBTQ and minority groups, we not only need to ensure that the collection is accessible to all, but that it continues to grow and in turn show the increasingly national and transnational contributions of Houstonians.”

A challenge from Gloria Steinem was issued to women to come forth and have their stories from the 1977 National Women’s Conference told. During the 2017 Reunion conference held at the University of Houston to mark the 40th Anniversary of the 1977 National Women’s Conference, over thirty women stepped forward to participate in having their stories of this historic occasion recorded for posterity. The recorded interviews capture stories from delegate attendees, many of which haven’t been heard for over 40 years. Women too young or unable to have attended the original conference also contributed their own personal stories, views, and insights into what the 1977 National Women’s Conference has meant to them and how the effects from the conference still resonate in their personal lives.

A challenge from Gloria Steinem was issued to women to come forth and have their stories from the 1977 National Women’s Conference told. During the 2017 Reunion conference held at the University of Houston to mark the 40th Anniversary of the 1977 National Women’s Conference, over thirty women stepped forward to participate in having their stories of this historic occasion recorded for posterity. The recorded interviews capture stories from delegate attendees, many of which haven’t been heard for over 40 years. Women too young or unable to have attended the original conference also contributed their own personal stories, views, and insights into what the 1977 National Women’s Conference has meant to them and how the effects from the conference still resonate in their personal lives.

Among some of the stories shared from the conference were from Peggy Kokernot Kaplan, one of the original torch relay runners during the 1977 Conference, Frances Henry, coordinator for state meetings leading up the National Women’s Conference, and University of Houston Law Professor Laura Oren, an attendee of the conference and early member of the Houston Area Feminist Federal Credit Union.

The Share your Stories campaign was recorded over two days, November 6-7, 2017 as part of the 40th Anniversary conference held at the University of Houston. The Share your Stories interviews can be found on the Audio/Visual Repository of the University of Houston Libraries. Additional information and materials on the 1977 National Women’s Conference can be found in the Marjorie Randal National Women’s Conference Collection of the Carey C. Shuart Women’s Archive and Research Collection.

This Is Our Home, It Is Not for Sale (This Is Our Home) is the title of Jon Schwartz’s 1987 documentary film that chronicles Houston’s Riverside neighborhood. While it is the story of a specific neighborhood in Houston, the themes of segregation, integration, white flight and disparity of city services are common elements in the history of many large American cities. This Is Our Home, which boasts an impressive 3 hour and 20 minute run time, includes interviews with some of Houston’s most famous and influential residents. The University of Houston Library Special Collections is home to the This Is Our Home, It Is Not For Sale Film Collection, which includes Schwartz’s original production documents, photographs, and production films, including B-roll footage and early edits of the documentary.

The original production used a dual reel system of motion picture and a separate fullcoat magnetic soundtrack that requires syncing to achieve a digitized video product. These films were at particular risk of loss due to the use of fullcoat magnetic soundtrack in production, making it susceptible to extreme vinegar syndrome. The films, used in the editing process, also featured numerous splices and missing portions which were utilized in edits of the documentary. In 2017, The University of Houston Libraries was awarded a Texas Libraries and Archives Commission TexTreasures grant to digitize 112 filmed interviews, and make them available via our AudioVisual Repository. These raw interviews provide insights both into the former and current residents opinions of the neighborhood that had undergone a drastic transition, they are primary documents of individuals struggling to discuss the complexities of race relations and emotional attachments to “home.”

The Story of Riverside

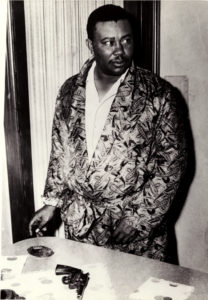

In the 1920s, members of Houston’s wealthy Jewish community were blocked from home ownership in Houston’s elite River Oaks neighborhood by anti-Semitic deed restrictions. In response to these restrictions, the community helped to establish the affluent Riverside neighborhood, located to the west of University of Houston’s central campus. The neighborhood, inhabited by Jewish and non-Jewish residents, became the center of Jewish culture in Houston and was home to many influential Houston families. In 1952, Jack Caesar, a wealthy cattle rancher, moved to Riverside by instructing his white secretary to buy a home and transfer the deed over to Caesar, defying deed restrictions that blocked black individuals from purchasing homes in the area. His arrival on Wichita Street was first met with a buyout offer from neighbors who had pooled their money. Caesar refused the offer, and a dynamite bomb was detonated on the porch of the Caesar family’s home. Unharmed and undeterred, the family remained in Riverside. With landmark Supreme Court cases including District of Columbia v. John R. Thompson Co. Inc. (1953) and Brown v. Board of Education (1954) finding segregating policies unlawful, more affluent black families bought homes in the neighborhood.

John and Drucie Chase standing in front of their Riverside home, designed by John Chase. From the This Is Our Home, It Is Not For Sale Film Collection.

In response to the influx of black residents and spurred on by unscrupulous real estate agents instigating anxieties about falling home values, many white residents sold their homes and moved to other areas of the city. Residents who hoped to maintain the neighborhood as an integrated community began a yard sign campaign that proclaimed “This Is Our Home, It Is Not for Sale.” While this movement gained national attention, it was not enough to slow the departure of white homeowners. Riverside continued to be shaped by forces including the departure of area businesses, the growth of UH and TSU campuses, construction of Highway 288, and the decision to locate a county psychiatric hospital in the neighborhood. In the late 1980s, white homebuyers attracted by Riverside’s beautiful homes, central location, and reasonable prices, began moving back into the area.

Through interviews with former and current residents of Riverside, This Is Our Home examines how anti-Semitism, racism, real estate agent-driven blockbusting, profiteering, white flight, and urban development projects created and continue to shape what was once one of the Houston’s most desirable neighborhoods.

Now Online

Jack Caesar, photographed with personal firearm following the bombing of his home (This Is Our Home, It Is Not For Sale Film Collection).

It is our hope that these materials will serve as a valuable resource, in complement to Schwartz’s documentary, and aid in scholarship around Houston. These primary source materials that trace the waves of segregation and desegregation dynamics in a large southern city and reveal the tensions related to population growth and demographic shifts. Not only do they document a segment of Houston history, but they also provide a profile of urban development with implications beyond the city and the region. Likewise, architectural historians, urban planners, historical geographers, and public administrators figure among the populations who may benefit from access to the complete, raw interviews.

All digitized raw interviews are available through the UHL Audiovisual Repository, and we have curated an online exhibition featuring an interactive map of the neighborhood highlighting interviews with Riverside’s residents. The full documentary can be viewed in the Special Collections Reading Room or purchased at http://thisisourhomeitisnotforsale.com/.

“The editors of your paper are Catholic, and have refused… to give this campaign radio time and press notices… We do not ask the Catholics to accept our program–we merely ask them to ‘live and let live.'” Letter from Agnese Carter Nelms to Jesse H. Jones, February 10, 1947, Planned Parenthood of Houston and Southeast Texas Records.

A new collaboration between the University of Houston Special Collections, the Department of History, and the Women’s, Gender & Sexuality Studies provided students with a unique opportunity to discover archival collections neatly aligned with their own areas of research interest.

Students from Dr. Zarnow’s Issues in Feminist Research class worked with librarians from our Special Collections to mine a variety of archival artifacts in collections from Carey C. Shuart Women’s Research Collection, the LGBT History Research Collection, and the Arté Publico Press Recovery Project to create an interactive timeline of primary sources discovered in their research. From materials tucked into archival folders, possibly overlooked by previous researchers, students uncovered items revealing the evolution of women’s social issues and concerns in the Houston and Gulf Coast region and the themes that connect these years of seemingly disparate work from a chain of individuals and organizations over decades.

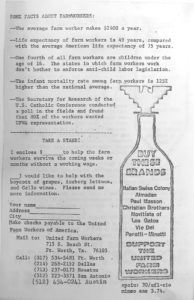

Boycott Gallo flyer, Houston Area NOW and Other Feminist Activities Collection.

Among the items highlighted from their research are correspondence from the 1940s, political flyers from the 1970s, and artists’ creations from the 1980s. In the Planned Parenthood of Houston & Southeast Texas Records, a 1947 letter from Agnese Carter Nelms to Jesse H. Jones, owner of the Houston Chronicle among other things, hints at the early conflicts between Planned Parenthood and the Catholic Church. A flier from the Houston Area NOW and Other Feminist Activities Collection recalls the gains won by César Chávez and the United Farm Workers but reminds us that, even now, there’s still blood in that wine. Meanwhile, photographs, posters, and other works of art from the Houston Gorilla Girls Records demonstrate how activism for gender equality in the world of art played out against the backdrop of 1980s Houston. Students worked to curate and describe these items and more, creating an interactive timeline (seen above) to provide users with visual and historical context while browsing their findings.

Photograph from the Houston Gorilla Girls Records.

If you are a faculty member, or student, interested in how the primary source materials housed in UH Special Collections can complement your teaching, learning, and research, see our website with more information on scheduling classes and utilizing our resources to learn more.