Approaching M.D. Anderson Library, you can’t miss Philip G. Hoffman Hall (PGH) nearby. Completed in 1974, it honors one of the university’s most important leaders and is a major landmark at the center of the campus. PGH and its neighbor, Agnes Arnold Hall, were designed by Kenneth Bentsen (UH 1952), a talented architect responsible for Houston’s Summit sports arena (1975) and other important buildings. PGH reflects the minimalist, modern style of the early 1970s. This style is not universally popular today, but formally this is a good building and I would like to show you why.

Philip G. Hoffman Hall from the east, behind Peter Forakis’ Tower of the Cheyenne. Photo by the author

Despite its large size, PGH is an elegant building. The strong horizontal lines visually lower its height. The façade is based on a grid, of course, but like a tartan plaid, the elements are interwoven, with some lines projecting and others suppressed. This is a subtractive composition where layers of the building are peeled away—slightly at the upper levels where, within each bay of windows, the projecting concrete fins provide a continuous bass note for the rhythm of repeating window mullions behind. There is a more pronounced cutting away at the lower levels; this culminates in the deep ground-floor gallery facing the plaza and the breezeway that penetrates the center. The slightly sculptural, three-dimensional facade prevents this from being just another boxy modern building.

Bentsen’s attention to detail can go unnoticed unless you look closely. The concrete construction is left exposed—a common practice at the time—but concrete can be finished in many ways, from very smooth to very rough. It is not always done as well as it is here. Bentsen specified a slight texture and a warm color that is pleasing to the eye. The wall surface is scored by the repeating pattern of small holes left by the concrete pouring process. They form an almost imperceptible grid of dots that enlivens the surface of the building. The holes have to be there, but the designer decides how to arrange them.

PGH is also impressive because of the way it is scaled to fit the plaza in front of it. The building occupies an important place at a campus crossroads, and visually it commands both the plaza and the broad avenue that it overlooks on the west. PGH should be understood at an urban scale, not a human scale: It is supposed to relate to the size of the plaza, not the size of the people in the plaza.

PGH is worth another look the next time you pass by. Records of this and other Bentsen buildings are housed in the Kenneth E. Bentsen Architectural Papers in the library’s Special Collections Department, where they are currently being processed.

Cadillac Ranch (1974), copyright Ant Farm, Photo Doug Michels Architectural Papers

The Cadillac Ranch marks its 40th anniversary on June 21, 2014, only four days after the death of its patron, Stanley Marsh 3. In this iconic art installation near Amarillo, the counter-culture art group, Ant Farm (1968 – 78), buried ten Cadillacs nose-first in a field alongside the old Route 66 as an homage to the Cadillac tailfin.

Ant Farm was based in San Francisco but got its start in Houston. In 1969 the University of Houston’s College of Architecture hired two young architects, Doug Michels and Chip Lord, for a one-semester job as lecturers. They founded Ant Farm and moved to San Francisco when the semester ended.

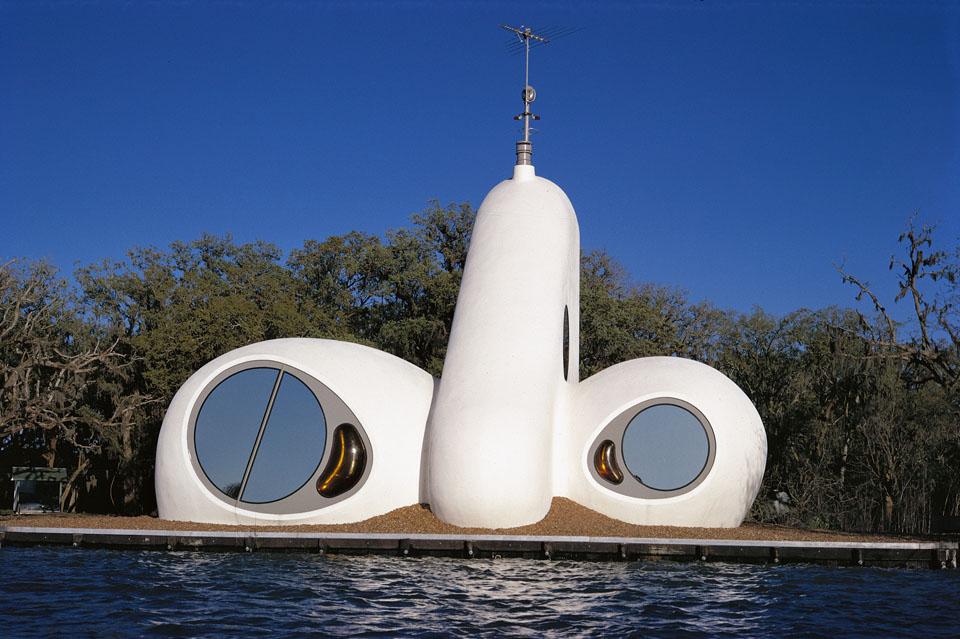

House of the Century (1972), copyright Ant Farm, Photo Doug Michels Architectural Papers

In 1971 Houston art patron Marilyn Oshmann commissioned the group to build a lake house on her family’s property near Angleton, Texas. The result, called the “House of the Century,” was an unconventional structure best described as “biomorphic;” it had no straight lines and recalled a living thing. In 1973 Playboy magazine published an article on the unusual house, calling it a “Texas Time Machine.”

Doug Michels, Stanley Marsh 3, Chip Lord (L-R), Cadillac Ranch 20th Anniversary (1994), Photo Doug Michels Architectural Papers

Among the readers was Stanley Marsh 3, an eccentric Amarillo businessman who often placed large outdoor art installations on his ranch. He invited Ant Farm—which by then included Curtis Schreier, Hudson Marquez, and others—to come to Amarillo and make some art for him. Their creation celebrated the love of the automobile and the open road that is at the heart of American popular culture. Cadillac Ranch made Ant Farm famous, inspiring a song by Bruce Springsteen (1980) and a Hollywood movie (1996).

In 1978 Doug Michels returned to Houston where he created a futuristic media room called the “Teleport” for businessman Rudge Allen. Michels’ Star Trek-inspired media room was published extensively. The Allen family donated the room to UH in the late 1990s, and it was reinstalled in the architecture building. Michels reunited with his Ant Farm colleagues in 1986 to create the flying Thunderbird car sculpture outside the Hard Rock Café on Houston’s Kirby Drive (now demolished).

Michels’ life came full circle in 1999 when the UH College of Architecture brought him back as a lecturer. He continued to practice architecture and design in Houston until his death in 2003. The university acquired Michels’ papers and drawings, and they now form the Doug Michels Architectural Papers in the library’s Special Collections Department.

The buildings that define the edges of Cullen Family Plaza—Roy Cullen (1939) and the Science Building (1939), designed by Lamar Cato, and Ezekiel Cullen (1950) by Alfred Finn—are the University of Houston’s original buildings. They were designed in a style usually called “stripped classicism” or sometimes “WPA modern” (so called because it appeared on many post offices and other government buildings erected by the Works Progress Administration during the Great Depression).

Stripped classicism is a “transitional” style because it represents a bridge from the traditional Greco-Roman classical architectural style to the modern style. In the 1930s, the modernist revolution swept the fields of art and architecture. Architects who practiced in the traditional styles felt the pressure to conform to changing popular tastes. Their solution was to transform the well-known classical architecture for those seeking something more modern.

The Parthenon by Frank Durr / CC BY-NC-ND 2.0

Classical architecture has a distinctive rhythm of solid and void—the masses and the gaps between the masses. In the ancient Greek Parthenon, the best known classical temple, the roof is supported by a row of columns with voids between them at regular intervals. The columns have grooves known as “flutes.” The columns support carved blocks called “capitals.” Modern architecture, however, is distinguished by its formal abstraction. The modern architect reduces the design to its formal essentials—a geometric box, for example—and avoids the superficial detail found in most traditional styles.

Proponents of stripped classicism abstracted the classical style by eliminating the ornament on the surface and making the building look more flat and two-dimensional. Stripped classicism was much more formal and conservative than other modernist styles of the day, which made it acceptable for public buildings.

The relationship between the university’s original buildings and the classical style that inspired them can be seen in this picture of the Science Building, although E. Cullen and Roy Cullen have similar details. Marching across the face of the building is a series of vertical masses separated by voids with the same regular pattern as a classical temple. To achieve this look, the edge of the second floor between the windows (the “spandrel”) is treated as part of the window frame and visually disappears. The window openings suggest continuous voids.

It’s easy to see references to the classical temple in the building’s details. The areas between the windows are carved with shallow grooves to represent the column flutes, and above the grooves a row of circular depressions suggests the capitals. The building’s limestone cladding also helps the viewer make the connection with the ancient stone temples.

Stripped classicism appeared in the 1930s and already looked dated by the time E. Cullen opened in 1950. The style was too fussy and conservative for the postwar era. But public tastes change. In the six decades since, the university has come to appreciate the architecture of its original buildings. When Shepley, Bulfinch, Richardson & Abbott designed the expansion of M.D. Anderson Library (2005), they looked to E. Cullen for inspiration. The main building’s transitional style has proved to be more enduring than anyone expected when the building was completed.

The following continues a series of contributions from Dr. Stephen James, who works with the Architecture and Planning collections here at the University of Houston Special Collections. Dr. James holds a Ph.D. in Architectural History from the University of Virginia and for many years was a lecturer at the University of Houston College of Architecture.

Our look at campus architecture today begins with Cullen Family Plaza, a favorite gathering place at the University of Houston. The plaza honors the Cullen family, whose patronage and leadership have shaped the university from its earliest days. Located in front of the Ezekiel Cullen Building, it is—along with the nearby Anne Butler Plaza in front of the M.D. Anderson Library—the social heart of the campus. Both plazas are relatively recent additions to the campus and resulted from a major overhaul of the university’s campus planning principles in the mid 1960s.

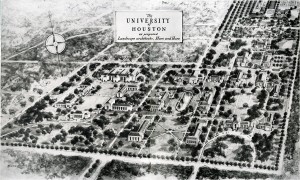

The campus was laid out in the 1930s by the Kansas City landscape architecture firm of Hare & Hare, which also designed Houston’s Hermann Park. Hare & Hare created a very formal, axial plan for the university, with the main buildings arranged in a rectilinear fashion and aligned symmetrically on either side of a centerline or axis. Several such axes can be seen in a 1930s rendering of the master plan from the Library’s Special Collections Department and in a 1967 aerial photograph from the UH Digital Library.

1967 aerial view shows UH buildings arranged around several formal axes, from the UH Photographs Collection and available for download in the Digital Library

This type of formal, axial planning, which dates back to ancient Rome, is used with monumental public buildings and is intended to convey a sense of grandeur or importance (think of the Mall in Washington, D.C.). The traditional architecture of the buildings represents the important public institutions housed within. Their predictable arrangement implies a reassuring sense of order, and their large scale makes the viewer seem insignificant in relation to these institutions. Formally, the spatial void in the center (the lawn or mall) is not meant to be inhabited; it reinforces the buildings that define it and helps tie the ensemble together.

The events of the 1960s changed public attitudes toward authority. Such formal planning became unpopular, as architects tried to humanize public institutions and make them less intimidating. Many campuses took on a “suburban” appearance by using more naturalistic landscape design and less rigid building placement.

These trends influenced the University of Houston, which abandoned its original master plan in 1966 to give the campus the casual, park-like character that it has today. Planners placed new buildings such as Farish Hall (1970), McElhinney Hall (1971), and Hoffman Hall (1974) across the important axes to create small plazas that might become centers of public activity in their own right, rather than simply reinforcing the importance of the buildings around them.

Cullen Family Plaza in the 1970s, shortly after its completion, from the UH Photographs Collection and available for download in the Digital Library

Cullen Family Plaza resulted from this change in 1972. Landscape architect Fred Buxton replaced the elliptical reflecting pool in front of E. Cullen with a large water pool that spanned the distance between the Roy Cullen and Science Buildings. Dramatic water jets introduced a dynamic element that balanced Lee Kelly’s large metal sculpture called “Waterfall, Stele, and River.” Farish Hall, completed shortly before the plaza, provided the necessary enclosure on the west side. In the four decades since, the landscaping has matured to soften the edges and further isolate the plaza from the distractions of the campus.

The UH Digital Library’s University of Houston Buildings Collection is an excellent resource for anyone looking for more information about the history of Cullen Family Plaza.

The following comes to us from Dr. Stephen James, who took a moment from his work with the Kenneth E. Bentsen Papers to reflect on the recent passing of Bentsen and his legacy.

The University of Houston lost a distinguished alumnus and friend last week. Kenneth E. Bentsen (Class of 1952) was an architect and a gifted designer. He made beautiful buildings that pleased the people who used them. He built a large and important architectural practice that earned the respect of his profession. Today his many buildings shape the environment of Houston and other Texas cities.

We see his work every day. At the University of Houston he designed Agnes Arnold Hall, Philip G. Hoffman Hall, and the Brown wing of M.D. Anderson Library. At the Texas Medical Center, he designed additions for Baylor College of Medicine, renovated the original buildings of the M.D. Anderson Cancer Center, and did most of the new buildings for Texas Children’s Hospital. Even the parking garages benefited from his talent.

Bentsen worked exclusively for large commercial and institutional clients. He designed two high-rise buildings downtown, the Southwest Tower for Bank of the Southwest and the Sheraton Lincoln Building. Both have been demolished. His best-known work in Houston was The Summit, the city sports arena where the Rockets played until Lakewood Church acquired the building. He created buildings in Galveston for UTMB and in Austin for the State Bar of Texas and the University of Texas School of Business. There were many others—too many to list.

Perhaps his most important work of architecture is one that Houstonians rarely see. Bentsen created the master plan and designed many of the buildings for Pan American University in Edinburg, Texas. Now called the University of Texas-Pan American, it is one of the most important educational and cultural institutions in the Rio Grande Valley. Influenced by the Philadelphia master, Louis Kahn, Bentsen established a distinctive regional style for the campus that the university has maintained to this day. Even without his significant body of work in Houston, this project alone would have been a formidable legacy. Very few architects get the chance to design and build a university campus.

Bentsen was born into a prominent family in the Rio Grande Valley, where his father, Lloyd Bentsen, Sr., was a successful rancher and businessman. His brother, Lloyd Bentsen, Jr., had a successful business career in Houston and was for many years a U.S. Senator from Texas. His son, Kenneth Bentsen, Jr., was a U.S. Congressman from Houston. Rather than follow his father and siblings in a business or ranching career, Bentsen pursued his passion for architecture. He often credited his success to his training at the University of Houston and spoke highly of two of his teachers, Donald Barthelme, Sr. and Howard Barnstone, both celebrated Houston architects.

Earlier this year, the University of Houston Libraries acquired all of Bentsen’s professional papers and drawings. This collection, the Kenneth E. Bentsen Architectural Papers, is now being processed and will be housed in the library’s Special Collections Department.