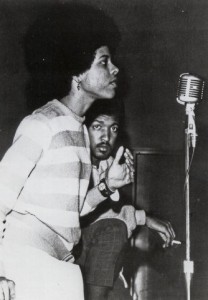

Lynn Eusan (image available for high resolution download at our Digital Library)

Earlier this month the University of Houston community cut the ribbon on a new and improved stage at Lynn Eusan Park. This new stage will provide improved sound, lighting, better sight lines for audience members, and will inject new life into a park named in honor of one of UH’s own. Lynn Eusan was a member of the Spirit of Houston, organizer of the Committee on Better Race Relations, founder of the Afro-Americans for Black Liberation (AABL), charter member of Alpha Kappa Alpha (UH’s first black sorority), and, probably most notably, the first African-American homecoming queen at UH and, as best we can tell, the first African-American homecoming queen elected in the South not from a historically black college.

The year was 1968. College campuses around the nation were centers of dissent and quickly becoming laboratories for social change. The University of Houston was certainly not Columbia, certainly not Howard, but if one thumbs through the Daily Cougar editions from the autumn of 1968, it drives home that the atmosphere on campus certainly reflected the ferment in Houston and other cities at home and abroad. In the midst of protests against police brutality, foreign policy, and parking fees (which I’m sure today’s students would find just shocking), the election of a homecoming queen seemed about the most apolitical and innocuous event taking place on campus. However, frustration was beginning to form as more and more students of different races seemed to be attending parallel universities separate from one another and the race for homecoming queen would become a stage for these divides to play out.

Lynn Eusan’s candidacy was noteworthy not only because of the color of her skin, but also because she had no major Greek support or backing. When the Daily Cougar asked why she was running for homecoming queen, Eusan replied, “I feel it is an honorable, very respectful position that any girl would be honored to have. I feel that there is not enough representation of non-Greek minorities on campus.” She was not alone. An ad running regularly for another candidate in the Daily Cougar urged students to, “Forget the Greeks. GO LATIN!”

The day of the election, the Daily Cougar ran an editorial (pictured here) imploring the student body to get over their “hang-ups” regarding color, to “exercise student power,” and elect a queen that “would represent… a liberal-minded, progressive student body.” A coalition of student groups and organizations rallied around this idea of a racial integration that broke down the walls of these parallel universities and they turned out to vote.

Eusan was already involved in arguably larger social justice issues being tackled by the AABL on campus and in the community. She worked to help establish and promote the new S.H.A.P.E. Community Center, she contributed to Voice of Hope (a newspaper covering the African-American community in Houston, they would later establish a scholarship in Eusan’s name), and her AABL organization would be instrumental in establishing the African American Studies program here at UH. Therefore, her candidacy, campaign, and eventual crowning as homecoming queen became more a sign or emblem of a movement building on campus rather than some prize won in the end.

In retrospect and compared to her work, it seems almost trivial. A crown. A tiara. Some flowers. For one moment, though, on the floor of the Astrodome on November 23, 1968, a coalition of students who had previously felt stripped of their voices rallied around a queen celebrating in disbelief.

Only three years later, in 1971, her life would come to a baffling and tragic end. The University of Houston would dedicate the park in her honor in 1976.

While the cultural and racial novelty of her being crowned homecoming queen will likely remain the lead attached to her life and legacy, the social and ethnic diversity that constitute the University of Houston in the 21st century is due in no small part to her work. No. Racism has not been eliminated at UH, but we are not alone in carrying that burden. However, as one of the most ethnically diverse research universities in the nation, reaping the benefits from its truly integrated global village on a daily basis, UH owes a debt to a movement that championed a woman like Eusan for a title like homecoming queen.

Here in Special Collections our University Archives offer a handful of items related to Eusan for study. In addition to the aforementioned back copies of the Daily Cougar, we are pleased to offer a number of items that may be of interest. Our African American Studies Records have materials related to a tribute to Eusan, the UH Photographs Collection holds the photo featured above and can also be found over at the Digital Library, the President’s Office Records hold reams of notes, articles, and correspondence providing a blow by blow record of AABL protests and their “ten demands” (as well as the ire and passions of a divided community), and Professor Patrick J. Nicholson Papers outline the work behind the scenes to establish what would eventually become the African American Studies program.

Here in Special Collections our University Archives offer a handful of items related to Eusan for study. In addition to the aforementioned back copies of the Daily Cougar, we are pleased to offer a number of items that may be of interest. Our African American Studies Records have materials related to a tribute to Eusan, the UH Photographs Collection holds the photo featured above and can also be found over at the Digital Library, the President’s Office Records hold reams of notes, articles, and correspondence providing a blow by blow record of AABL protests and their “ten demands” (as well as the ire and passions of a divided community), and Professor Patrick J. Nicholson Papers outline the work behind the scenes to establish what would eventually become the African American Studies program.

As we ring in a new era for Lynn Eusan Park, take an opportunity to explore and celebrate a life that tells a story unique to the University of Houston. As we move into summer and the campus din quiets down, remember that we remain open for study and eager to assist your research.